According to the saying, the sins of the fathers are supposed to be visited upon the sons. But in Bai Jobe Njie’s case, and several other parents, it was the other way round when their children were implicated in a failed coup.

As far as Bai Jobe knew, his son, Modou Njie, a former private in the Gambian army, was in Germany in December 2014. He had not seen him for years, but he was sure that Modou would have told him if he was coming home. He even had no idea that the State House in Banjul had been attacked on December 30 as the coup plotters tried to remove President Yahya Jammeh.

The retired civil servant thought it odd that several family members called him on the morning of December 31 to ask him the whereabouts of Modou. He is in Germany, he told them. Even when he started hearing rumours about the attempted coup, it never occurred to him that his son was involved.

Reality started sinking in when a relative who said he had reliable information told him Modou was among the people who had attacked the State House. While he was still trying to absorb the shock, there were reports that Modou had been killed. As family and friends arrived to condole with him, Bai Jobe knew that his ordeal had just started.

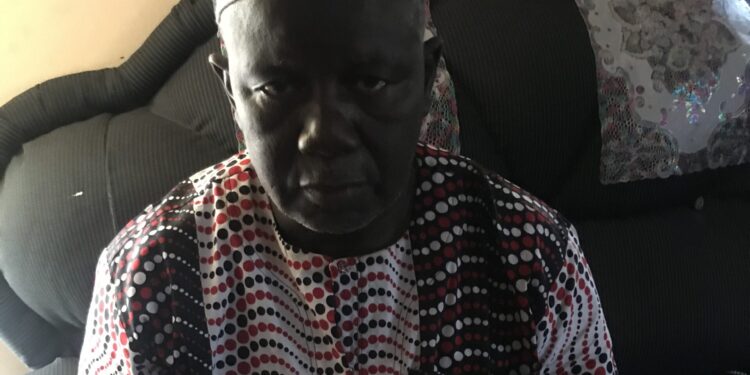

“I always knew they would come for me. I just didn’t know when,” he mused as I spoke with him at his home in Talinding. “They” were officers from the National Intelligent Agency (NIA).

Therefore, Bai Jobe was not really surprised when, four days later, he noticed a white truck parked outside his compound at about 2am. He quickly called his wife and instructed her to lock the door behind him. He did not want the officers to enter the house because he knew that they were usually rough during their arrests. They were already banging on the doors and windows, terrifying his family.

When he stepped out, one officer asked him whether he was Modou Njie’s father. When he answered in the affirmative, he was informed that he was being taken to the NIA headquarters. He was not given a chance to change his clothes or hand his wife money for food.

At the NIA building, he was questioned about the coup. He told them that he was not aware that his son was in the country, but they did not believe a word he said. He was ordered to empty his pockets, and then he was led into a room filled with the parents and relatives of other coup plotters.

The room was so crowded that there was no space to lie down. For three days, they were served only bread. Bai Jobe asked one of the officers if he could have rice instead because bread gives him constipation. He was told, “Eat it if you can. If you cannot, leave it.” On the fourth day, he was offered a plate of rice that cost him D25.

They were not allowed visitors, or even to move around. Sitting in one place affected his joints. Bai Jobe, who estimated his age to be about 65, found this forced immobility particularly difficult. He has worked his entire life. Even now, after retirement, he finds it difficult to sit idle and therefore operates a taxi to keep himself busy – and he is quite busy. He cancelled our appointment three times because he had to ferry his clients.

He and the parents of six other coup plotters got to know one another well during those seven months they were confined. He still remembers their names. He said they were not physically molested.

They were lucky. Several witnesses at the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission have told harrowing stories of innocent parents being arrested and sometimes tortured physically and mentally because their children did something the former president did not like.

Bai Jobe is a man of few words. His answers are short and precise, expressed without emotion. Asked about the health implications of sitting in one place for seven months, he responds, “Getting sick is obvious. I am not young, and we were there for a long time.”

On the day of their release, senior police officers, including then Inspector General of Police Ousman Sonko, came to humiliate them, lecturing them and telling them to teach their children manners before ordering them to go home. “How can we teach grown-ups manners?” he asks me. I have no answer for him.

When the confusion around the coup finally cleared, it emerged that Modou was in fact alive. He was in a group of Gambians in the diaspora, mainly in the US, UK, and Germany, who had plotted to overthrow Yahya Jammeh. Their attack on the State House failed and four of them were killed. The others fled. Modou was captured at the scene. He and five other soldiers were court martialled. In April 2015, Modou and two other soldiers were sentenced to death while the other three were given life imprisonment. In March 2017, AFP reported that the new president, Adama Barrow, had pardoned the coup plotters, including Modou Njie, and had them reinstated in the army.