By Siga Ndure in Banjul, The Gambia

and Mary Wasike in Nairobi, Kenya

siga.ndure@jfjustice.net, mary.wasike@jfjustice.net

“Don’t scream; just let them do what they want and leave.”

With tears running down her cheeks, the woman recalled uttering these words to two of her neighbours 13 years ago as they were sexually assaulted by security agents who had invaded her home. The neighbours had sought refuge in her house after their husbands were arrested, but instead ended up being assaulted together with her.

The words of this woman did not signal surrender; they were a means to survive because she knew that her attackers could do much worse, and get away with it.

The woman, a member of the Ndigal Muslim sect, originally from Kerr Mot Ali village in the Central River Region of The Gambia, knew well what it means to be targeted, to be persecuted by the state.

The women of the sect suffered many tragedies during the years they lived in The Gambia. They persevered the state’s persecution of their group members during the years of former president Yahya Jammeh, leading up to their forceful eviction from their homes in 2009 and eventual flight into exile in Senegal as their homes and property were snatched from them.

Ironically, they have for years been joined in an unholy alliance of silence with their tormentors to cover the shame and stigma associated with sexual violence. The assaults were such a well-kept secret that they did not make it to the pages of the final report of the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, the result of The Gambia’s truth-telling process as the country struggles to come to terms with the brutality of Jammeh’s two decades of dictatorship.

In fact, some victims never even told their spouses or close family members that they had been attacked. Silence was adopted to bury the shame the women and their families felt as a result of those attacks in January 2009.

The tribulations of the women of the Ndigal sect, whose members are sometimes known as the Seckens, stem from the controversy their group has evoked over the years. According to the expelled residents, Kerr Mot Ali was founded in 1777 by Muhammed Ali Secka in Senegal. He founded many villages such as this one, which were led by one of his sons. In 1996, Serign Basirou Secka (who migrated from Touba Saloum in Senegal) took over as the head of the village in The Gambia. When he died in 1998, he left his son, Muhammed Basirou Secka, in charge.

It was during Muhammed’s time that the sect started changing. He introduced a new way of worship called Haqikatul Munawara, which had rituals quite different from traditional and mainstream Islamic practice. Members of the Ndigal sect do not pray five times a day or fast during the holy month of Ramadan, like traditional Muslims; they only pray and fast when they get ndigal (divine intervention). They do not follow the teachings of Prophet Muhammed, but instead follow those of Muhammed Basirou Secka (Serign Ndigal). The followers were also said to be required to pledge allegiance to the leader.

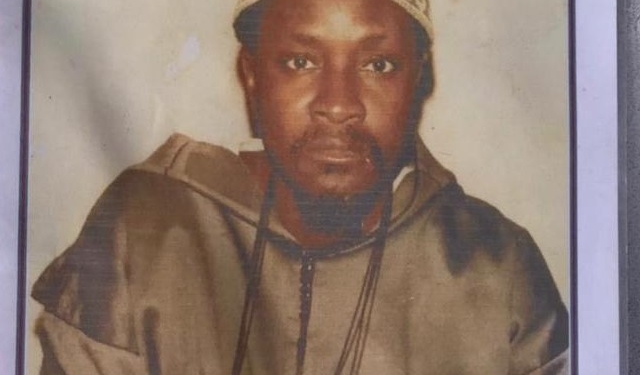

Muhammed did not do anything without ndigal. This is the reason he and his followers did not see the need to pray five times a day. He later adopted the title of Serign Ndigal for himself. His followers wear a pendant with his picture around their necks and have pictures of him in their rooms and places of worship.

Muhammed soon ran foul of the Supreme Islamic Council, which considered the Ndigal sect’s way of worship to be heresy, and state authorities. In 2002, several allegations of drug trafficking, illegal possession of a counterfeit currency printing machine, and intentions to overthrow the Jammeh were levelled against Muhammed Basirou Secka and he was arrested. However, he was later released due to lack of evidence. His followers blamed his tribulations on his brothers, who were leading the other villages, just because they did not agree with his new way of worshipping. When he died, he left his son in charge of the affairs of Kerr Mot Ali.

Trouble for the sect erupted after Serign Ndigal’s death, when his brother from Touba (Senegal), Alieu Secka, decided to reopen a mosque in Kerr Mot Ali which had been closed. When the villagers rebuffed his efforts, Alieu sought the assistance of state authorities to forcefully restore the mosque.

In Januray 2009, armed security forces arrived to enforce a presidential executive order to ensure the mosque was opened and renovated. They arrested the men of Kerr Mot Ali. Some were detained for three days while others stayed in jail for as long as three weeks.

They were taken to MacCarthy, Njau, and Kaur prisons, where they said they were tortured. Some were subjected to hard labour and other forms of severe torture. Reports say several of them died as a result of the maltreatment.

Kumba Secka said her father was killed by the security forces after his arrest. Another victim, Momodou Lamin Assan Secka, whose father was one of the founding members of Kerr Mot Ali, said he was ordered to unload a truck full of cement bricks.

It was during the time when most of the men had been arrested that the women, who had been left alone, were attacked by the security agents.

After many years of silence, some of the women agreed to tell their stories to Journalists For Justice. One woman said security agents who had arrested her father came back at night to assault her and her mother.

Another one suffered a miscarriage after she was beaten, gang-raped, and made to perform other sexual acts the whole night at MacCarthy prison.

One woman recalled that she was was cooking lunch for her family when security agents broke down her door. She was blindfolded, beaten, and raped by one of the men. Her pregnant sister, who was at home with her, suffered the same fate. She suffered ill health throughout the remainder of her pregnancy and had complications during childbirth.

Yet another woman recounted how she was arrested with her one-month-old baby. She was raped and tortured and could not have any more children. She still suffers pain in her pelvis.

One woman was raped in front of her 11-year-old daughter.

Yet none of these stories came out during the hearings of the truth commission, and none was recorded in the TRRC’s final report because the women kept silent about the attacks. For many years, most of the women kept the details of their individual encounters to themselves, a secret they could not dare divulge even to their families. The stigma and shame attached to rape victims in the Gambian society was too heavy for them to bear.

In 2017, the villagers took the matter of their displacement to the Gambian High Court, which ruled in their favour and ordered that they be allowed to return to their homes and that their property be returned to them. However, the order has yet to be enforced.

Most of the sect members said they had registered with the TRRC, but a large number complained that they had not benefited from the reparation programme. They also complained that although they had given their statements to the TRRC, they were not given an opportunity to testify during the commission’s public sessions.

Yunusa O.S. Ceesay was the only victim from Kerr Mot Ali who was called to testify at the TRRC. He gave a vivid description of the attacks on the village and how security agents later burnt down the homes of the sect members, forcing them to seek refuge in Senegal. The villagers left all their property, including livestock and land, which were later taken over by Alieu Secka and his followers from Senegal.

Ceesay did not say anything about the sexual assault on the women and girls because the victims had never talked about their ordeal.

Yet the abuse was widespread. During its engagements in Kerr Mot Ali, JFJ’s partner, the Women’s Association for Victims‘ Empowerment, found that almost every female in the village had been affected. All the 21 women interviewed in January 2022 said they were raped or made to perform other sexual acts by the armed security agents, who sometimes invited civilians to participate. Some had suffered multiple assaults, in addition to being verbally and physically abused.

The TRRC’s recommendations on Kerr Dot Ali say the members of the Ndigal sect still living in exile in Senegal should be allowed to return to their village and that their property should be returned to them. The government is also asked to enforce the judgment the sect members obtained from the High Court.

Some of the villagers have accused the TRRC of failing to conduct a thorough investigation of their case, instead basing its conclusions on the testimony of just one member of the sect. JFJ’s efforts to obtain the commission’s explanation on why many details of the Kerr Mot Ali incident, particularly the many cases of sexual and gender-based violence, did not come up during its investigation failed as the commission was winding up its operations. No official authorised to speak for the TRRC was available to comment.

Despite their suffering, the people of Kerr Mot Ali are open and welcoming. They readily speak about their tribulations of many years. They freely admit that their dearest wish is to get their home back and see that justice is served to their tormentors.

The displacement has wreaked havoc on their lives. Many of the villagers are unable to send their children to school or get access to healthcare services. They deal with identity issues, living as refugees in a foreign country.

Jammeh wielded religion as a potent weapon to solidify his dictatorship. Over the years, he would appear in public dressed in a white khaftan, cultivating the image of sainthood and purity. He would always carry a Koran and prayer beads.

The former president ordered the arrest, detention, and torture of religious and other leaders perceived to challenge his authority or religious position or beliefs. He used the Supreme Islamic Council to legitimise his actions and enforce the brand of Islamic practice he propagated. His executive directives granted the council powers beyond the confines of the law.

Members of sects such as Ndigal, which did not espouse the Islamic version of worship that Jammeh favoured, were persecuted by the Supreme Islamic Council and state agencies. Their refusal to recognise any human authority except what is ordained by divine inspiration, and total submission to the authority of their leader did not sit well with Jammeh, who had elevated himself to the position authority and divinity usually attribute to a deity.