By Zainab Jobarteh

Officially, Yahya Jammeh fell from authority when he lost the presidential elections of December 2016. But most Gambians know that his grip on power had started slipping months earlier, in April of that year, when opposition parties rallied the citizens to join in protests demanding electoral reforms.

They were tired of the injustices that were getting worse by the day. Arbitrary arrests. Detention without trial. Enforced disappearances. Extrajudicial killings and torture. Gambians decided to do something about it. They went to the streets.

Jammeh’s government reacted predictably, arresting protesters and opposition leaders, and harassing them. However, most Gambians did not react predictably. Although many were arrested, jailed, and tortured, and some, like Ebrima Solo Sandeng, paid with their lives, they refused to be intimidated. Crowds still turned up on the streets to continue the protests.

The sustained demonstrations eventually spurred the divided opposition into action, bringing the parties together in a coalition that presented one candidate. Adama Barrow went on to pull a surprise win against Jammeh and precipitated the dictator’s flight into exile in January 2017.

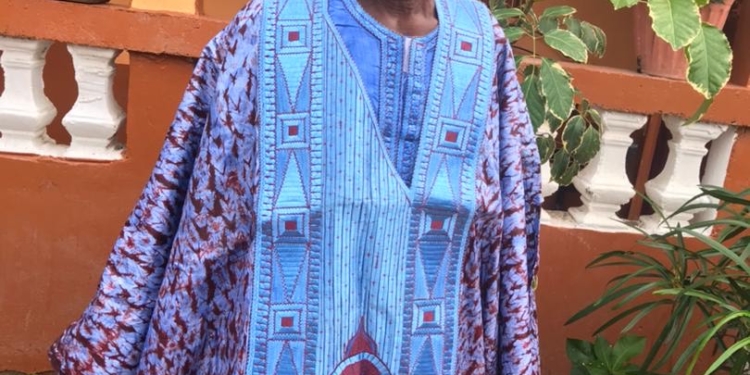

Many Gambians paid a high price for the freedom the country is now enjoying. Kafo Bayo and his family know this well. A supporter of the opposition United Democratic Party (UDP), he did not shy away from joining the protest march scheduled to kick off from Westfield on April 14. Even when he and the other UDP supporters realised that the other opposition parties had backed out, Bayo did not go away.

“We saw paramilitary vehicles coming towards us, but we did not run. A military officer told me to board their vehicle. I refused to obey him because I had not done anything wrong. His colleague came from behind and hit me on the back. I felt dizzy and they dragged me into the vehicle,” said the 68-year-old father of 11.

Eleven protesters were arrested that day and taken to the Police Intervention Unit (PIU). Bayo will never forget the instructions of then Inspector General of Police Ousman Sonko to the PIU officers guarding the prisoners. “Go and finish them,” he said as the detainees were herded into the offices of the National Intelligence Agency (NIA) for questioning.

The officers were interested in finding out if the protesters were acting on the orders of UDP leader Ousainou Darboe.

“Once one of the officers questioning me heard my surname, he asked if I am a Mandinka. I said yes, he shook his head and told me they were going to kill all of us.” Then the military officer hit him hard in the chest. He still gets chest pain.

Many Mandinka support UDP, and Jammeh had always been suspicious of the whole community. He had on several occasions called them names on national television.

When the detainees were taken to write their statements, the officers started beating Solo Sandeng, who had been leading the protest. “They took him away and I heard him cry out that they were killing him. They continued beating him until his voice faded away and I could no longer hear him,” Bayo said.

He and two of his colleagues were taken to “Bambadingka”. This was a special place at the NIA headquarters where most torture sessions took place. Several witnesses at the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) described the place as a dark room with no windows.

“They put a plastic bag over my face, then tied my feet and hands,” he said as tears ran down his face. He was dragged into a room and tie to a table. Then the beating started.

“I do not know what tool they were using or whether it was connected to electricity, but I cannot describe how I felt when it touched my skin.” He was left lying on the table and eventually fell on the floor. Until recently, the scars from the beating were visible.

He received no medical care when he regained consciousness or at any other time during the 14 days he was detained at the NIA offices. The prisoners were not fed for two days.

After two weeks, the prisoners were transferred to Mile 2 Prison, where they were locked up for another 14 days. All this time they were not allowed to wash themselves. Bayo does not remember how many days he spent remand, but one afternoon the 11 were transferred to McCarthy Prison in Central River Region.

It was hot at the prison and the area was infested with mosquitoes. The prisoners were transported to Mansakonko in Lower River Region for the court hearings. They sat in the open back of a truck, exposed to the wind and sometimes heavy rain.

‘We were sentenced to three years in prison without labour. The prison officers at McCarthy tried to make us to work, but we stood our ground,” Bayo said.

Three months later, they were returned to Mile 2. Bayo suspected that they were sent back because they were useless to McCarthy as they could not be put to work on the farms, like the other prisoners, due to the court order.

Bad as McCarthy was, Bayo preferred it to Mile 2. He said prisoners were served food that “even animals would not eat. You put it in our mouth and quickly washed it down with water because you did not want to taste it.” The cells were so small the prisoners could not stand upright.

The protesters were released after Jammeh lost the elections in December 2016. However, Bayo did not feel free because he was no longer safe in his own house. He received many anonymous calls advising him to leave the country because Jammeh was angry that the protesters had been released. He spent nights out in the bush because he was afraid to sleep in his own house. He only felt safe after Jammeh left the country.

Bayo was sad that his daughter Amie suffered too. Amie, now 26, was arrested on one of the days her father was being taken to court. According to Amie, she had called her mother on her way from school to find out whether she was in court. Her mother told her not to go to the courthouse because paramilitary officers were everywhere. “She asked me to wait for her at Ousainou Darboe’s gate.”

In those days, on the occasions the protesters were taken to court, UDF supporters would don T-shirts decorated with their party’s symbols and assemble at Darboe’s compound to show their solidarity.

Amie said on that particular day, two paramilitary vehicles arrived carrying armed soldiers. People started running. “I could not run fast because I was wearing a tight skirt. Then a military officer threatened to shoot me if I did not stop.”

She and several other UDP supporters were arrested and bundled into a vehicle. The beatings started immediately.

“I tried to explain to them that I was waiting for my mother, but they would not listen.” The group of six adults and a months-old-baby was driven to the PIU headquarters and herded into a big hall, where the beatings continued. The officers did not care where they hit their victims. “They hit us all over the body.”

Eventually, they were separated and the men were taken away. At night, they were given mattresses to share. In the morning, the prisoners were splashed with cold water and whipped to wake them up faster.

They were made to sweep the entire camp and clean the toilets. As they worked, the soldiers insulted them and threatened them with sexual assault. Amie said the food was quite unpalatable. They were served white rice with dry fish at lunchtime, but not given any dinner.

On the eighth day of their incarceration they were taken to court. She did not understand what transpired but remembers that they were allowed to go home on the 11th day, when they went back to court.

Amie developed health complications due to the torture. She suffered from pneumonia because of the cold water poured on her and the fans and air conditioners that were left running all the days they were in the cell.