By Zainab Jobarteh

It took years for Fatou Suwa to know the identity of her husband’s killers.

And it is likely that she might never have known this if the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission had not been set up to investigate the abuses of the Yahya Jammeh regime.

Fatou’s long-held suspicions that her husband, Mustapha Colley, had been killed by government agents were finally confirmed when one of his murderers confessed during one of the commission’s hearings.

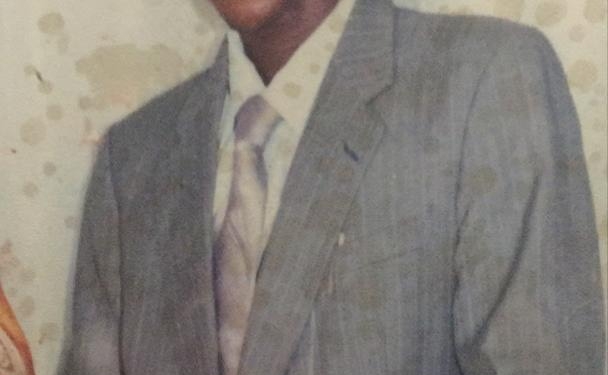

Mustapha was a soldier in the Gambian army and was posted to guard the State House. He had a promising career and seemed set for bigger things when he passed the qualifying examination to join the United Nations/African Union peacekeeping mission for Darfur, Sudan. Then just a month before his deployment, he was suddenly dismissed from the army.

Fatou, who lives in a tiny house with her three children, has never believed the reason her husband gave her for his dismissal: that he had failed to vote in the 2011 presidential election. She is convinced that he had voted. “I did not have a voter’s card when I got married to him, but he made sure I got one and persuaded me to vote for Jammeh.”

She still remembers the day in 2012 Mustapha, whose colleagues referred to as “Sergeant Colley”, went missing. Since his dismissal, he had been operating his “taxi”, transporting goods and people in order to earn a living and look after his wife and their three children.

On that fateful day, Fatou said her husband received a call from a stranger who said he needed to transport furniture to his new house. She was suspicious because the man had called twice. She though it was a trap because Mustapha had just been fired. She urged him not to take up the job, but he insisted that they needed the business. She never saw him alive again.

Fatou got concerned when she did not hear from him and called him on his phone after a few hours, but he was unreachable. She was worried but did not know what to do. Her worst fears were confirmed when his body was found in his abandoned vehicle. The police informed his brother, but Fatou only learnt of his death the following morning. A post-mortem showed that Mustapha’s neck had been broken.

She tried to follow up the case with the Serious Crimes Unit, but met with frustration at every turn. “It was like taking two steps forward and 10 steps back. I had to stop because I was afraid they would kill me the same way they had killed my husband.”

She has a simple explanation for her fears: “Jammeh was still in power.”

She describes Mustapha as a very private person. He had lost his mother at a young age and his father died shortly after they got married. He liked to keep to himself, listening to his music. “He was a kind and considerate man.” He did not talk to her about his work, so she could not imagine why he was sacked, but she was convinced that his death had something to do with his job.

Her suspicions that her husband’s employer was involved in his death were strengthened by the fact that not a single government official helped his family in any way after his murder. Fatou said she knew they had a hand in his death, but did not know how to prove it.

Then on July 24, 2019, the truth finally came out. Omar Jallow, a soldier in the Gambia Armed Forces, told the TRRC that he had participated in the execution of Mustapha and many others.

“Mustapha Colley was a soldier working at the State House. He was dismissed from the army. I do not know why. One day, Nuha Badjie [a soldier] gave an order that we should meet at the base. When we met there, Nuha Badjie brought out a paper that had a car registration number on it and a telephone number. He said it belonged to Mustapha Colley and that I should write down the number. He gave the original copy to Sulayman Sambou [a soldier] and asked us to go out on the roads and search for Mustapha Colley. Sambou left first. When I set out, they called and said he had found him [Mustapha Colley] and taken a town trip with him,” Jallow said.

The commission’s lead counsel, Essa Faal, asked Jallow if they had been told what to do with Mustapha. “Nuha Badjie said Yahya Jammeh said we should find Mustapha Colley and kill him. Sambou packed an old television and told Mustapha that he needed his services to take the television to Kololi. When they arrived at Kololi, they carried the television into Sambou’s room, and that was where we jumped him.”

Asked to specify who attacked Mustapha, Jallow said: “Nuha Badjie, Mustapha Sanneh, Modou Jarju, Nfansu Nyabally, Malick Manga, and Omar Jallow [the witness]. We put him on the ground and suffocated him. We held his nose and strangled him.

“We then put him inside his taxi and Sambou drove the vehicle to the road leading to Jabang. We got into our pick-ups and followed. When we got there, we parked the taxi at a corner and left it there with the body inside.”

The men who executed Mustapha have killed many other people. They are known as the Junglers, the hit squad that Yahya Jammeh used to carry out extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances.

Fatou’s family is among the many that have suffered due to Yahya Jammeh’s excesses. She lost her husband early in their marriage and therefore had to give up many of the hopes and dreams they had shared.

When Mustapha married Fatou in 2010, she was a widow with two children. She said he was a responsible family man and looked after her children as if they were his own. His death changed her life and that of their children forever, ushering them into a period of suffering they had never imagined could befall them.

After her mourning period, she had to move to a small house. It was difficult to provide for her family because she had depended on her husband. Now she had to do petty trading to pay rent and buy food. Her children had to transfer to public schools because she could not afford the fees at their private schools. They had to adjust to their new life, living in poverty.

Fatou remembers one very trying incident that made her think the world had turned its back on her. Her eldest daughter fell in school and fractured her hip. The doctor informed her that the girl needed to go to Senegal for specialised treatment. Her efforts to get help failed and the child’s condition continued to deteriorate. “Then I was introduced to a lady who volunteered to pay for her treatment and we went to Senegal. She was under treatment for a month before they operated on her. My daughter and I spent almost a year in Senegal,” she said.

Fatou does not follow the TRRC proceedings because she thinks they serve little purpose other than to open up old wounds. “I do not think they will do anything about the death of my husband.” She held off registering at the TRRC until recently. One of the mandates of the commission is to pay reparations to the victims of Jammeh’s regime. Resigned to her fate, she said she is content to watch things run their course.