By Janet Sankale

Justice conversations in Africa are complex, emotional, multifaceted, and highly nuanced. Justice is embedded in the society’s political, social, and economic structures. It was inherited through the colonial-era system, which replaced the traditional mechanism. This has stifled the ability of Africans to assert their place in the justice system.

The justice question is further complicated by the growing number of African governments that are not only shrinking the space for civic activism but are also destroying the backbone of democracy and inclusive development.

The continent, therefore, is in dire need of a free space to express its views on issues of justice.

That is what the cartoon exhibition, “Justice Through African Eyes”, seeks to provide. And it seems appropriate that the first display showcasing a selection from a rich array of some of the continent’s most visible cartoonists to present Africa’s justice narratives and voices was staged in The Gambia, a country that is making great strides in politics and freedom of expression after 22 years of brutal and suffocating dictatorship.

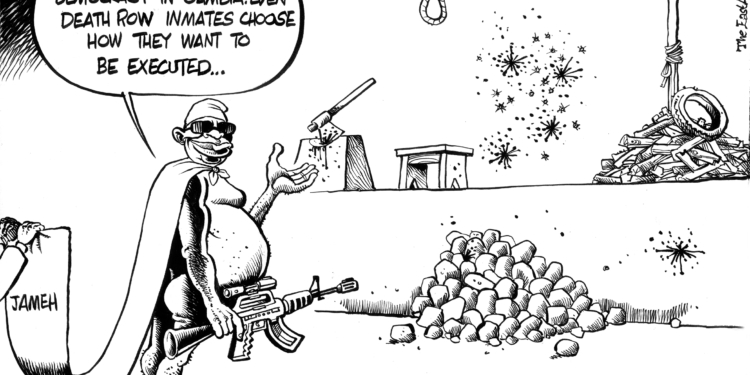

Anyone with a basic knowledge of the history of The Gambia under the iron fist of Yahya Jammeh will not be surprised that the host country’s only contribution to the cartoons on display at the Alliance Française de Banjul between February 9 and 15, 2022 were several blank slates. These were not just empty spaces; they were an eloquent testimony of the effect of Jammeh’s decades-long tyranny on freedom of expression.

Right from the moment the former soldier seized power in a bloodless coup in July 1994, Jammeh made it clear that he viewed freedom of expression and the press as a real and credible threat to his rule, and set about devising means to muzzle and silence the media. Journalists were killed, arrested, tortured, and disappeared. Media premises were attacked. Harsh laws to curtail the media were enacted. It is no wonder that no political cartoonists would be intrepid enough to try to ply their trade while living in The Gambia in the intervening period until the dictator fled into exile in January 2017.

The cartoon exhibition was organised by The Hague-based Journalists For Justice (JFJ) in collaboration with Gambian civil society organisation, Women’s Association for Victim’s Empowerment (WAVE).

Speaking during the launch, Kwamchetsi Makokha, JFJ’s Progamme Adviser, asserted that the Gambian space was not empty, and that the blank slates had been deliberately left for Gambian cartoonists to claim their space to speak on behalf of their people.

He said JFJ’s first call for Gambian cartoonists did not elicit any response because the previous regime’s system of repression silenced all critical voices.

“However, there were cartoonists around the continent who were caricaturing Yahya Jammeh, his administration, because of the safety of not living in The Gambia. They had the freedom to criticise him and his administration,” Makokha said.

The Gambia was the first stop of the exhibition, which has incorporated cartoons from all over Africa. The collection, also to be displayed in Nigeria, Uganda, and Kenya, presents visual illustrations and commentary on the important state of the African justice system, a new approach to convey and simplify the message around justice. The use of a combination of images and words, welded together by artistic wit and wisdom, gives cartoons efficiency and influence in creating a shared understanding of issues.

The presentation includes contributions from household names such as South African Jonathan Shapiro, Burkinabe Damien Glez, Tanzanian Godfrey Mwampembwa (Gado), Sudanese Ali Obaid Alamin, Ivorian Karlos Guédé Gou (Liade Guedé Carlos Digbeu), and Kenyan Paul Kelemba (Maddo).

In a press release, JFJ said the exhibitions aim to harness and showcase provocative interpretations of justice debates as seen through the eyes of African cartoonists.

“We seek to aggregate critical voices from a rich array of some of the continent’s best known cartoonists to present how Africans have experienced and debated justice,” added Rosemary Tollo, JFJ’s Programme Director.

The organisers said the exhibition seeks to expand African conversations on accountability beyond safe and acceptable narratives by curating the discourses into a coherent body of voices on why issues of justice and reparations continue to be a difficult subject.

The exhibition also featured a panel discussion on cartoons and freedom of expression. Makokha, who moderated the debate, said considering The Gambia’s small population, the killings, torture, and disappearances visited on its citizens by Jammeh’s regime qualify to be classified in the same category as the crimes committed during the Rwandan Genocide and the violence in Darfur, Sudan. He expressed concern about the culture of silence in The Gambia and sought suggestions on how it can be broken.

Gaye Sowe, Executive Director at the Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa and the guest speaker at the panel discussion, said one way to help break the cycle of silence is to train Gambians to express themselves through cartoons, apart from writing for newspapers and talking to radio stations.

“Not all of us like reading and the use of cartoons will help in simplifying the message,” he noted, adding that the use of cartoons should be incorporated in freedom of expression.

Another way is to eliminate the legal barriers that criminalise freedom of speech.

“Freedom of expression is narrated narrowly. There is a need to interpret it clearly to enlighten and sensitise people. To achieve meaningful reform, we need to drive change that contributes to political will and ensure that it permeates to ordinary people,” Sowe said.

Tida Jobe, who campaigns to give voice to victims of atrocity crimes, said freedom of expression was threatened during the past regime, leaving Gambians with no space to voice their opinions.

Giving the example of her life, she said she could not report her husband’s death out of fear of reprisal as Jammeh had made it taboo to speak out.

She said she was relieved when she was able to speak about her pain when the Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparations Commission was established.

Jobe suggested that the culture of silence can be broken at community level through counselling services offered in appropriate languages.

Journalist Saikou Jammeh, who is also a former secretary-general of The Gambia Press Union, said it is the responsibility of the citizens to recognise and embrace the right to freedom of expression because any restrictions placed on such freedoms affect everyone, not just victims and journalists.

The cartoon exhibitions will be buttressed by an online digital tour due to be unveiled in March 2022.